Edgar Degas & the Bellelli Family

The road to Capaccio. On foot, it's about 25 minutes from Borgo La Pietraia to the village.

Capaccio is the kind of small Italian hill town where you can plan to just run into someone. It was the free day for guests of our spring tour in Cilento. A few had decided to rent a car and drive to nearby Matera. Others were sleeping in or relaxing on the terrace.

Around 11am, I walked up to the old town from Borgo La Pietraia, hoping to see Gaetano Puca, the local historian. A Capaccio native, he has written over a dozen books about Capaccio's's history from the days of Spartacus, to the town's founding in the Middle Ages by people fleeing coastal pirates, to the Italian patriot Costabile Carducci. As I had hoped, he was in the main piazza overlooking the mountains toward the sea, chatting with vendors in the weekly street market.

"Professore!" I called out and he squinted at me. He said hello in a friendly enough way, but I could tell he didn't recognize me.

"Scariati," I said referring to my grandmother's family name, "di New York."

He threw his hands up in the air and laughed. We chatted periodically via Facebook, but it had been a year since he had given me a walking tour of Capaccio to show me all the places my grandmother and her siblings had lived and worked. Immediately he began introducing me to the vendors as a daughter of Capaccio who lives in New York. Then he asked if I had some time to walk with him and see something he hadn't shown me on my last visit.

We paused in front of an elementary school where children's voices rang out from the open windows. Then the professor gestured toward the opposite side of the street.

"Palazzo Bellelli," he proclaimed, taking a deep breath. An older man sat in front of the 12-foot high doors. He greeted the professor then picked through keys dangling from a ring until he found the one that opened the palace doors. He pushed his stubbled chin forward indicating that I should peer inside.

Inside the entrance of the abandoned Palazzo Bellelli, Capaccio.

The stone entryway had iron rings embedded in the walls for tethering animals. On my right, a staircase led up to a crumbling corridor where nature had crashed through the walls and settled into the house. I started snapping pictures. As I moved deeper inside, the worried professor cringed and warned me repeatedly to protect my head.

Birds swooped in and out between the crumbling plaster and the orchard of feral fruit trees just beyond the palazzo's walls. Everything smelled like stone and wet leaves. Some corners were impossibly dark while others were brightly lit from sunlight plummeting through the broken ceiling.

This had been the residence of the Bellelli family, the local nobility from when Southern Italy was part of the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily. Built in the 17th century, the palazzo has now been abandoned for over thirty years. At first glance everything seemed smashed and broken, though elegant details were intertwined with the decay.

I consciously switched my gaze from gawking outsider to art historian. I tried to catalog what I saw in my memory by identifying the styles I saw; the hand-painting ceiling, the columns topped with bouquets of sculpted flowers, terracotta tiles painted to look like ancient mosaics and walls painted with expensive pigments of blue and Pompeiian red. In contrast to the otherwise humble stone dwellings of the Cilento countryside, this palace was lavish and opulent.

Photo credit: Danielle Oteri

The Bellelli family were one of thousands of land owning families around Italy before it was unified as a single nation. Today the only remaining Bellelli in the region is Baronessa Cecilia Baratta Bellelli who leads cooking classes for our tour guests.

Though the lineage has dwindled and the palazzo is abandoned, the Bellelli were immortalized by Impressionist painter, Edgar Degas. Considered Degas's first great masterpiece, "The Bellelli Family", which hangs at the Musee D'Orsay in Paris, the painting immortalizes the painter's Italian relatives.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) The Bellelli Family 1858-1867, Oil on canvas

Degas is so deeply associated with France and Impressionism that his Italian roots and their influence on his artwork have often been overlooked. During the French Revolution, Degas's grandfather left France and settled in Naples (then a very French-influenced city ruled by the Bourbons) and married an Italian woman. Though penniless when he arrived, Ilario Degas amassed a great fortune and purchased a 100-room palazzo, which he bought from the Pignatelli family floor-by-floor. Degas went on to inherit the palazzo much later in his life. Today it is the 3-star Hotel Maison Degas.

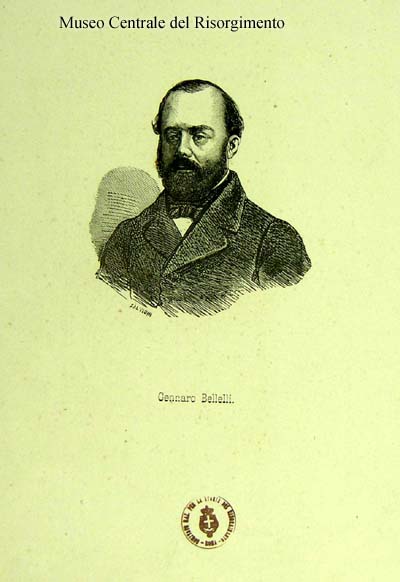

The painter's father was born in Naples and most of his relatives lived there. In his early twenties, he was deeply influenced by what he saw in Italian museums. Degas had particular affection for his aunt Laura, married to Gennaro Bellelli, who was born and raised in the now broken palace in Capaccio.

Palazzo Bellelli, Capaccio. Photo credit: Danielle Oteri

Studies for the famous painting were likely done in Florence where the Bellelli family was living when Gennaro was exiled from Naples for his anti-monarchist activities. However, during this relatively brief exile, Degas also spent time with his aunt Laura and the couple's daughters Giovanna and Giuliana at their family home, Palazzo de Gas in Naples, close to the Church of the Gesù.

Could Degas have visited the Palazzo Bellelli in Capaccio? Though there is no specific record of his visit there, we have journal notes about his travels in Southern Italy where he painted Mount Vesuvius and visited (and likely sketched) ruins at Pompeii and Paestum. Given that the temples at Paestum are only 8 miles from Capaccio, it becomes a more likely scenario that the painter visited the Bellelli's palace.

Ruins of the 6th century B.C.E. Greek temples looking toward Capaccio. Photo credit: Danielle Oteri

"The Bellelli Family" painting is a portrait of estrangement. Laura is dressed in mourning clothes for her father, the patriarch of the Degas family, whose portrait is include in the painting, hanging on the wall behind her. The two young girls look elsewhere while their father, Gennaro, sits at a desk, staring coldly into space, his back to the viewer, there, but not there.

Degas worked on sketches of Laura and the girls in Florence for an intense 8-month period in Florence and Naples. The final painting seems to be the result of many sketches and studies done over ten years between Paris and Italy. There is a blue wall in the palace at Capaccio with a flower pattern that is eerily similar to the wall shown in the painting. Could Degas, after a visit to Capaccio, have added in this detail as an homage to the home from which they were also estranged?

The flower pattern on the ruined wall of Palazzo Bellelli in Capaccio is similar to the wallper in Edgar Degas's "The Bellelli Family" painting. Photo credit: Danielle Oteri

The palace reflects the most beautiful design conventions of the 18th and 19th century so it's absolutely possible that the Bellelli home in Florence or Naples had similar decorations. But, I am already digging more deeply into Degas's passage through Paestum to find out more about what he saw and did there.

I also have a personal tie to Palazzo Bellelli. The professor told me that in the early 1900s, my great-grandfather had worked for the Bellelli family as their carriage driver. My grandmother had fond childhood memories of the Marchesa who lived there at the time, a kind woman who would let her eat as much fruit as she wanted to in that now overgrown orchard. During the 1920s the poverty in the area, especially among those like my grandmother who had lost a parent to Spanish influenza, meant that having your fill of food was a rare and wonderful treat.

The gardens and orchard outside Palazzo Bellelli Photo credit: Danielle Oteri

For now, the palace remains abandoned with haunting relics. Inside the kitchen just beyond the entrance, Professor Puca pointed out the bread paddles still propped up against the walls of a large wood burning oven. Just beyond it is a large mixing sink used for combining flour and water together to make the daily bread. He suggested that maybe I come back in the fall with a hard hat so I could look more closely at the all the details.

Inside the main entrance of Palazzo Bellelli Photo credit: Danielle Oteri

Corridor of Palazzo Bellelli Photo credit: Danielle Oteri

UPDATE

In Fall 2016, I was leading another group tour of CIlento. While guests were busy making ravioli during our cooking class with Cecilia Baratta Bellelli, I told her the story of my grandmother having loved the Marchesa for having let her have her fill of fruit in the orchards. Cecilia turned around, pointed to the painting hanging just behind her and said,

"That's the Marchesa right there. Her name was Marietta."